Yesterday I was lucky enough to take a new class at the Piedmont Wildlife Center, Poisonous Plants. The Director of Education at the Piedmont Wildlife Center, Sarah, has been growing a poisonous plant garden for the last two years specifically to teach people about poisonous plants, and this year it was finally ready.

We started off with the parsley family. We examined the differences between Queen Anne’s Lace/wild carrot and two of its poisonous cousins, poison hemlock and water hemlock. Both are extremely deadly and can be fatal even in very small quantities. Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), which contains several toxic alkaloids, was used in ancient Greece to execute prisoners, including Socrates. One particular alkaloid in hemlock, coniine, appears to be the main culprit, shutting down the central nervous system and causing respiratory collapse and death. The effects wear off in 48-72 hours, but death occurs quickly without artificial ventilation.

Death by poison hemlock is relatively peaceful, but its close relative, water hemlock (Cicuta) contains a toxin named cicutoxin which stimulates the central nervous system, causing hallucinations, delusions, and seizures. The toxin is so potent that poisoning has been reported even in children who only used the hollow water hemlock stems as whistles.

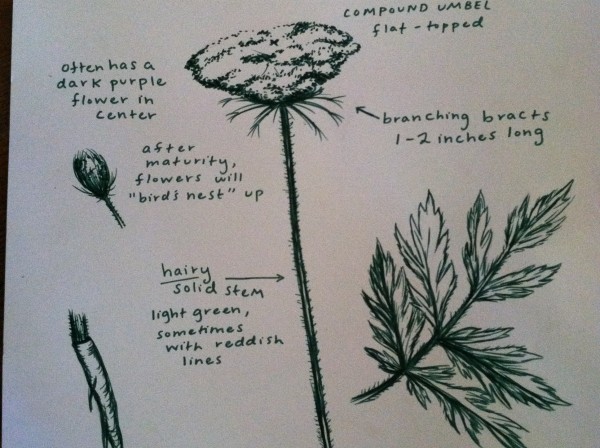

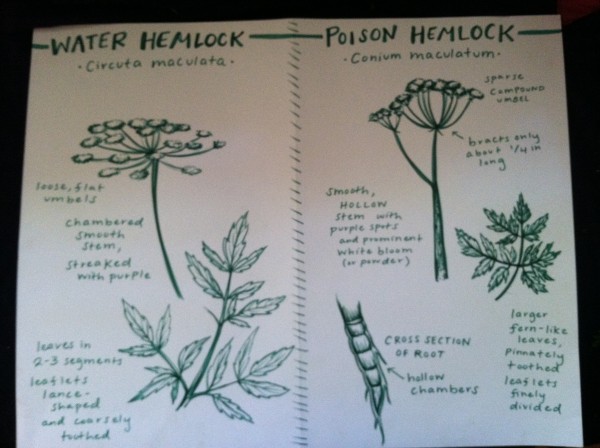

The dangerous toxicity of the hemlocks, along with their physical similarity to other plants, including wild carrot, mean that wild plants in the parsley family should be consumed with caution, and only experts in plant identification should attempt to identify these plants for consumption. I myself plan on staying far, far away from wild plants in the parsley family. One of Sarah’s interns drew out some beautiful diagrams demonstrating the main differences between the three plants (although my photos could have been a bit better):

The top of the first slide is cut-off, but that is the wild carrot poster. Major differences between the plants’ physical appearances are as follows:

Wild Carrot:

- compound umbel; flat topped

- branching bracts 1-2 inches long

- often has a dark purple flower in the center

- after maturity, flowers will “birds’ nest” up

- hairy solid stem- light green sometimes with reddish lines

- leaflets are deeply and erratically lobed

- root is solid and pithy- smells like a carrot!

Poison Hemlock:

- sparse compound umbel

- bracts only about 1/4″ long

- smooth, hollow stem with purple spots and prominent white bloom (or powder)

- larger, fern-like leaves, pinnately toothed leaflets that are finely divided

- root is hollow and chambered

Water Hemlock:

- loose, flat umbels

- chambered, smooth stem, streaked with purple

- leaves in 2-3 segments, leaflets are lance-shaped and coarsely toothed

Sarah has been unable to grow poison hemlock successfully, but she brought some wild carrot for us to look at:

and she was also able to harvest some water hemlock by the Eno River. She actually cut into the root to show us its hollow chambers:

Pretty cool, but you wouldn’t catch me doing that!

After examining the hemlocks, we left Sarah’s cabin and walked through the woods to the poison plant garden. On the way, Sarah asked us to point out any poison ivy plants we spotted, although we stopped doing that about 15 feet into the woods, because otherwise we wouldn’t have gotten anywhere. I’ve already posted quite a bit about poison ivy on this blog, so I’ll pass over that plant for now. Sarah also showed us some yellow buckeye (Aesculus flava) growing near the path, which we had also examined during a Plant Guild class a few weeks ago. Sarah said yellow buckeye is also called horse chestnut, although a bit of research indicates that horse chestnut is actually a different species- Aesculus hippocastanum versus Aesculus flava. The small tree we looked at was definitely yellow buckeye though, as horse chestnut leaves actually look a bit different.

Yellow buckeye bears some superficial similarity to Virginia creeper (which I’ve never thought to photograph because it is so common here), mainly because they both have five leaves. A closer examination reveals however that yellow buckeye leaves don’t completely circle the stem the way Virginia creeper leaves do, and the teeth are much finer. The pattern of the veins is also different. Also, obviously, yellow buckeye is a tree and not a vine.

On the way to the poison plant garden, we also stopped in what I call the “Allergy Field” (because of how I and a number of other people always start sneezing within a minute of entering it) to look at some horse nettle (Solanum carolinense):

As you can see in the slides above, horse nettle is covered in spines on both the stem and leaves. Like some other plants called nettle (Purple dead nettle for example), horse nettle is not actually a nettle. It belongs to the nightshade family, like tomatoes. In fact, another name for horse nettle is “wild tomato”, although that moniker is rather unfortunate and better not used, lest it give the wrong impression of the plant’s edibility. Although horse nettle fruits bear a passing resemblance to tomatoes, the effects of eating them are more likely to mimic those family members that give the nightshades their nasty reputation. Deadly members of the nightshade family include mandrake, belladonna (also called deadly nightshade), and henbane. Tobacco is also in the nightshade family.

Like all members of the family Solanaceae (including tomato, potato, and eggplant), horse nettle contains solanine, a toxic alkaloid that can cause death if ingested in a large enough quantity. Solanine is concentrated in the leaves, stems, flowers, and green unripe fruits of nightshade plants, although the quantity of solanine is low enough in tomatoes that the unripe fruit can be eaten safely. Green potatoes should not be eaten due to the risk of solanine poisoning, and wild potatoes, which have a higher concentration of solanine than cultivated potatoes, should not be eaten at all.

After our detour through Allergy Field, we arrived at the poison plant garden. Man, was it sunny. And hot. And sunny. Very, very sunny. My brain also chose that moment to remember that doxycycline, which I am taking to treat Lyme’s Disease, causes photosensitivity. And that I had forgotten to wear sunscreen. Luckily I was wearing my ever-present, wide-brimmed Tilley hat along with long pants, but my arms were unprotected and I hoped that we wouldn’t be spending too much time in the blazing sunlight of the poison plant garden.

The first plant we looked at was Dogbane (Apocynum), which Sarah contrasted with a similar plant next to it, milkweed (Asclepias).

Dogbane:

Milkweed:

According to Wikipedia, Dogbane’s genus name “Apocynum” means “poisonous to dogs” (it is also poisonous to people), and presumably that is where the common name came from, too. All parts of the plant are poisonous. It has some similarity to milkweed, which is not poisonous when harvested and prepared properly, and is in fact delicious (we ate some at the most recent Wild Harvest class), although it should be boiled, and only young shoots should be eaten. Probably the easiest way to tell them apart is that milkweed has soft fuzz on the stem and underside of the leaves, while dogbane is smooth. Also, apparently dogbane leaves squeak when rubbed together, although none of our group was able to coax a squeak out of the plant. Additionally, milkweed stalks are hollow and green inside, while dogbane stalks are solid and white or cream inside. There are other, more subtle differences, but those are probably the most obvious distinctions to look for. They both contain white milky sap (which is NOT an indication of toxicity- dandelions have white milky sap as well). Additionally, one page I found states that if the plant tastes bitter, spit it out. Common milkweed should not be bitter, and you may have eaten dogbane or one of the bitter milkweeds. But don’t worry- as long as it was just a taste, you should be fine.

Next we looked at Canada moonseed (Menispermum canadense), which I think is a great name:

It looks somewhat similar to wild grape (Vitis rotundifolia), but unlike the edible wild grape, all parts of Canada moonseed contain a (potentially fatal) toxic alkaloid named dauricine. The similarity is fairly superficial, though. The shape of the leaves is different from that of wild grape (Canada moonseed is more angular and squared off at the bottom), and the leaves are not toothed (wild grape leaves have prominent teeth). Additionally, moonseed seeds are crescent (maybe that is where the name came from?), while wild grape seeds are round.

After the moonseed, we looked at Lobelia siphilitica, which is also apparently called “Great Blue Lobelia”. The “siphilitica” part comes from an old belief that the leaves would cure syphilis. However, all parts of the plant contain poisonous alkaloids, so you have to ask yourself whether it is really worth the risk to try it!

Next we looked at Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum), which has many names, including “devil’s apple” and “American mandrake”, which are pretty badass labels for this cute looking little plant:

It looks like it has chubby little cheeks or something, and I hereby declare Mayapple the winner of the “Cutest Poisonous Plant” award. It produces a fruit that actually looks more like a (slightly wrinkly) lemon than an apple, and the fruit is not out yet in May. However, eating this plant takes some care, because every part of it is toxic except the ripe fruit. If the fruit looks more like a lime than a lemon, it is not yet ripe enough for safety. The seeds should be removed, and never eaten. Unfortunately, animals generally descend on these fruits as soon as they are ripe enough to eat, so it is reportedly difficult to get one for yourself.

The last plant we looked at was yellow jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), which is a vine:

The flowers are yellow and trumpet-shaped. All parts of the plant contain toxic strychnine-related alkaloids, and the sap may cause skin irritation. Children have been poisoned after mistaking the plant for honeysuckle and sucking out the nectar (it is toxic to honeybees as well). Yellow jessamine is the state flower of South Carolina (North Carolina’s state flower is Dogwood).

That’s it! It was a great class, and one I had been looking forward to for months. I was a little bummed that we didn’t get to see poison hemlock in person, but it was still a great class. Now I am tempted to check local botanical gardens to see if any of them grow poison hemlock! Plus, every time I spot a plant that looks like Queen Anne’s Lace, I stop to verify that it is that plant, and not (as I am hoping) its deadly cousin. So far no luck!

Great blog!

I spent the first half-century of my life in Raleigh and visited Eno River Park quite often. The festival in July was always fun.

Thanks for reviving good memories and for a most useful, informative, and very well done blog post.